Don’t get confused!

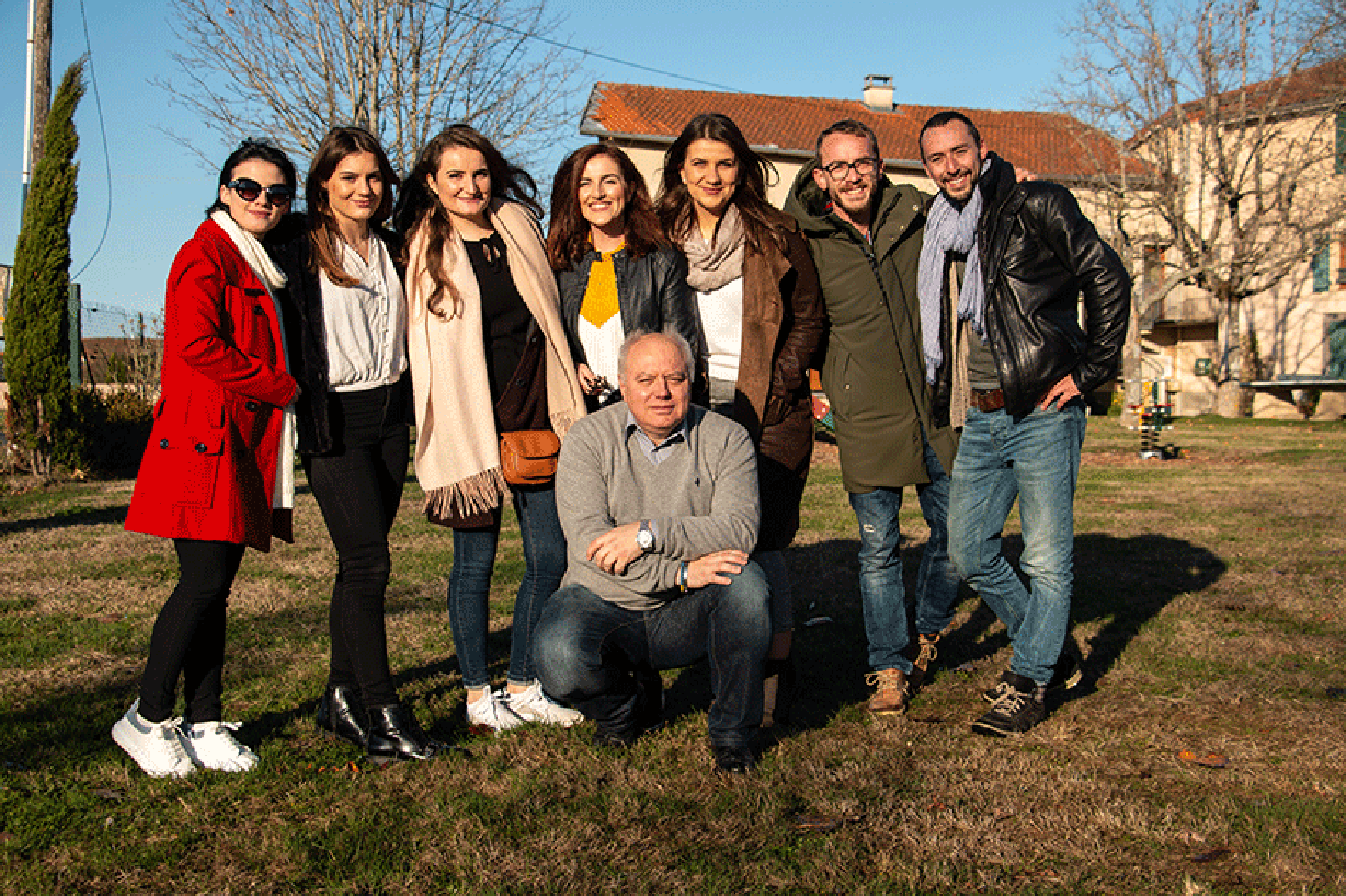

What is the Council of Europe and what does it do? The young journalism students of the seminar “Sur les pas d’Albert Londres” visit its headquarters in Strasbourg to find out.

There’s lots of room for debate at the Council of Europe. © Jana Kugoth

The Council of Europe, the Council of the European Union, the European Council, the European Commission… Giuseppe Zaffuto, press attaché of the Council of Europe, shakes his head. It’s no wonder people recoil at the sight of all these similar names. “Even journalists are confused,” he tells a group of journalism students during their visit of the Council of Europe’s headquarters in Strasbourg. It’s Giuseppe Zaffuto’s job to communicate to and through the press what the institution he works for actually does – and the results it achieves.

First of all, he explains that the Council of Europe is an intergovernmental organization like the NATO or the OECD and not an institution of the European Union. It doesn’t help that its flag and its anthem are now also used by the EU – Giuseppe Zaffuto smiles as he notes that the Council of Europe had them first.

Press attaché Giuseppe Zaffuto is passionate about his job. © Jana Kugoth

The Council of Europe’s mission is to make sure human rights, democracy and the rule of law are upheld in its 47 European member states. Its work is based on the European Convention on Human Rights, and the most widely-known of its bodies is the European Court of Human Rights. What is unique to this international court is that, after exhausting all judicial possibilities in their own state, individual inhabitants of member states can directly appeal to it.

In the Council of Europe, countries who share the same values meet to support each other in implementing them. The standards and instruments developed “help the states in the practical application of their values at the legislative level,” Giuseppe Zaffuto explains. They deal with issues like domestic violence, human trafficking, cybercrime and the protection of national minorities.

The Council is financed by 200 million Euros of contributions from member states. The largest five, whose languages also constitute the working languages of the Council, are France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Russia. Giuseppe Zaffuto himself is Italian, but states that his national identity takes a second seat behind his dedication to the intergovernmental goal. For him, one of the most important attributes needed to do his job is: “You have to like people.” The flexibility to be able to work with different people from different countries is important, too, as is the proficiency in a few different languages. “The more, the better,” he says, and states English and French as an absolute must. 2500 people currently work for the Council.

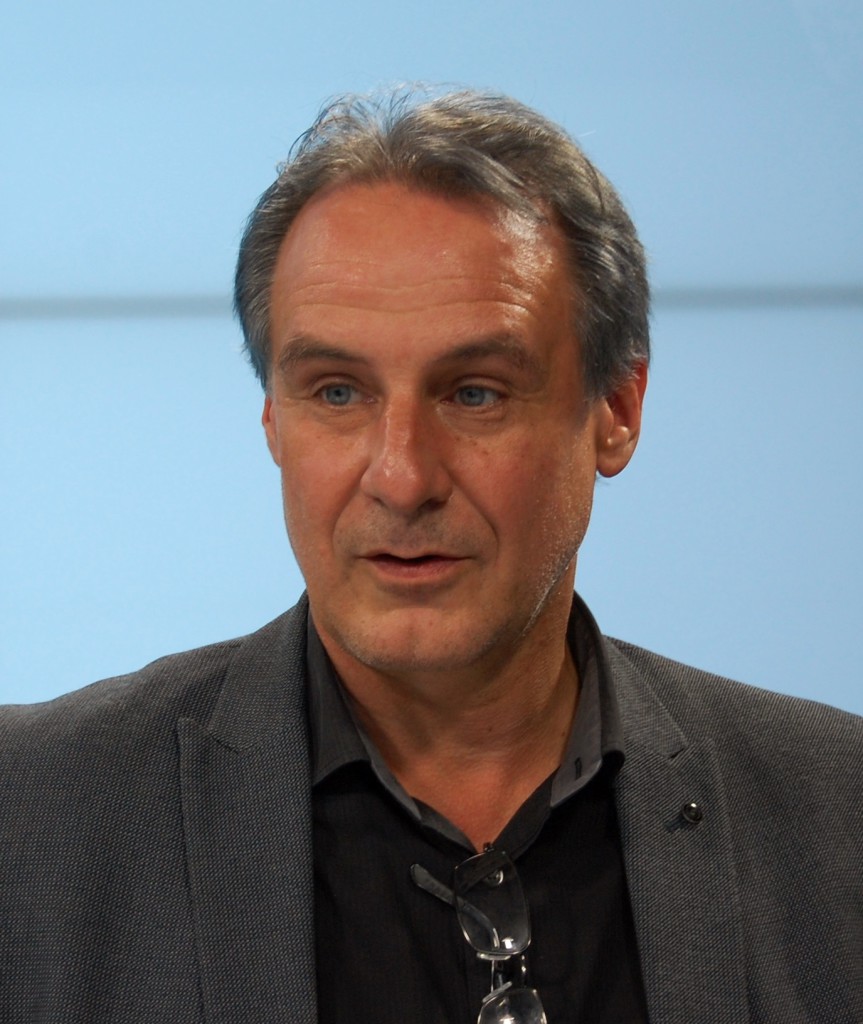

Ulf Ahlberg also works for the Council of Europe’s press department. © Barbara Hiller

Ulf Ahlberg is one of Giuseppe Zaffuto’s colleagues in the press department. He is the producer of the Council of Europe’s web TV journal. The seven-minute journal shows reports on developments surrounding the three main topics of the council: human rights, democracy and the rule of law. It is available in English with a dubbed version in both French and English. A dubbed Russian version is planned.

While public awareness of the issues dealt with by the Council is the press department’s prime objective, Giuseppe Zaffuto himself is not sure how important it really is for the public to be able to perfectly distinguish between his organizations and the others associated with Europe and particularly with the European Union. “I ask myself this question every day,” he says in response to journalism student Thibaud Roth’s question. “And the answer is: I don’t know. What I do know, however, is that it is important that people don’t use Europe as a scapegoat for things which are going wrong in the world but are beyond our influence. The more they know about the work of the different European institutions, the less likely this is to happen.”

Barbara Hiller